This summer, we’ve been traveling on our “design pilgrimage” as we call it.

I brought several books on the trip with me to give structure to my thoughts and writing. One was Experiences in Visual Thinking by Robert H. McKim, the classic how-to manual for anyone who wants to sharpen his or her creative visual thinking skills.

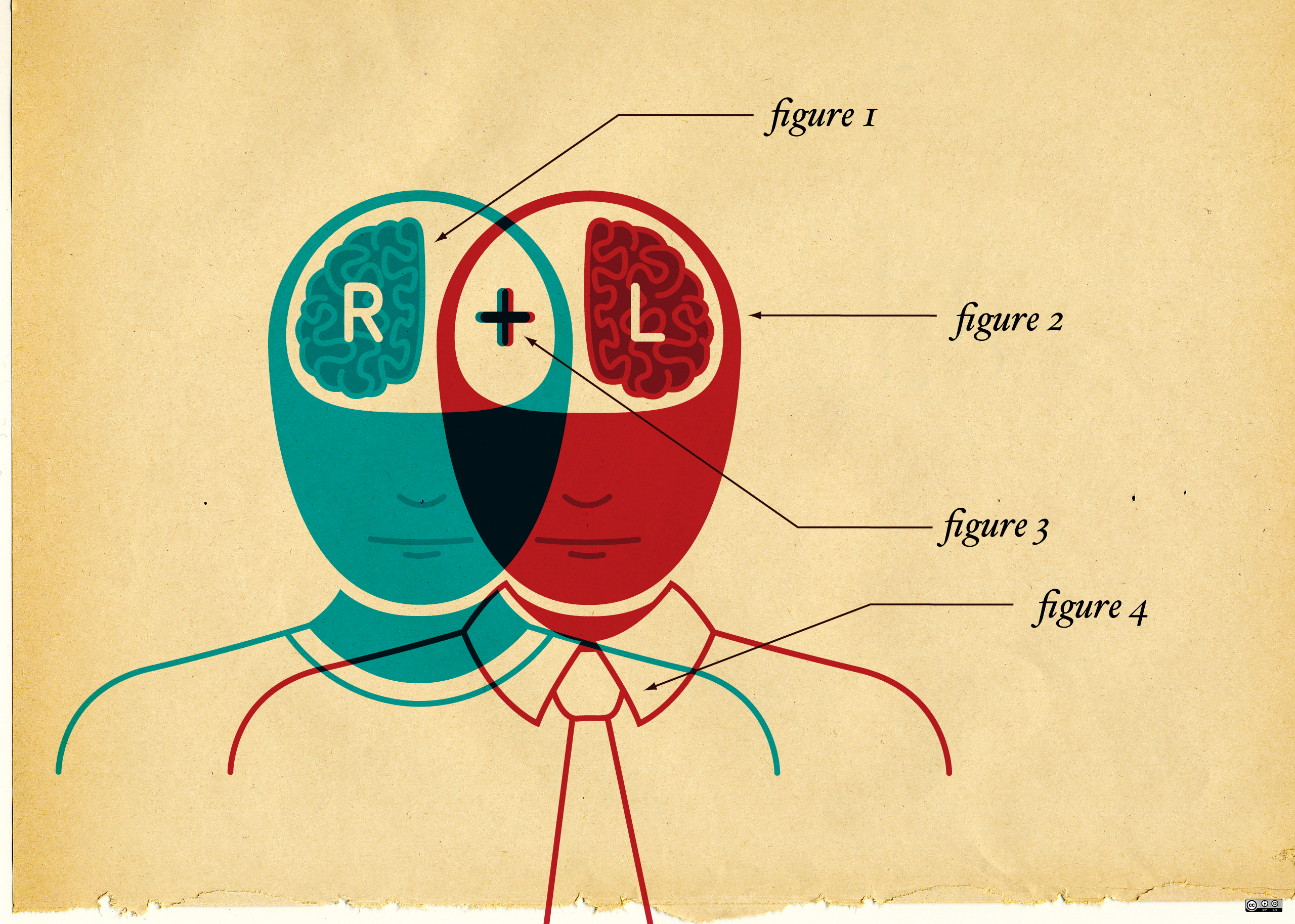

These are the methods of approaching any problem or situation using subconscious and conscious types of thinking. Visual thinking is a multifaceted skill and approach to any problem we have to solve on any given day.

We’re all born with the ability to harness our imagination, and we think most of our waking lives, but as McKim sees it, schooling, habits, thinking patterns and work life get in the way. We think broadly and unproductively. We believe the way we think about one situation applies to most other problems or assignments.

When I was a university teaching assistant, we new teachers had several sessions of training to prepare us for working with students and the various ways people think and learn. Most academics are logical and linear thinkers, but that’s merely a slice of the learning personalities in the world.

In one particularly useful session, the trainer was a professor and researcher who used neuroscience in his teaching methods. He said that all of one’s thinking life could be reduced to patterns we used in the grocery store (before Amazon, obviously!). The way we thought and acted on our thoughts in the store was the organizational patterns or thinking blueprint we probably applied to everything else in our lives, including university assignments. Some people are spiral thinkers, he said, they go in the middle and work their way out, with or without a list. Others work from the sides going up and down the aisles.

He gave us this information as a way to help us teach and empathize with students. Everyone uses patterns in their thinking and we apply them to most aspects of our lives. Raising our awareness about the types of thinking, he wanted us to understand that just because someone doesn’t take what we think to be logical notes it doesn’t mean they’re not absorbing and using the lecture content meaningfully.

We approach our design problems in similar ways to our approach to the grocery store and McKim’s tool kit remains valuable for all of us visual solutions people.

The pivot for thinking takes place as we look at our world. Using McKim here, seeing is what most people do; perceiving is what most successful visual thinkers do.

What’s the difference between perceiving and seeing?

Seeing

Seeing is looking at the world and our surroundings as is. We use and apply thinking blueprint and go about our day solving problems or creating solutions. We look at an assignment or problem. We research what others say about it and come up with solutions. It’s practical, efficient and reliable. This is often called deductive thinking. It means you apply general observations about the world to particular problems.

But, seeing as a thinking tools is rarely innovative.

Perceiving

Perceiving, on the other hand, is active with multiple steps and involves all of what McKim calls “operations” in our brains. Here are some key facts about the process of perception:

- Active and ‘down below.’ Let’s say you are given a creative brief with an assignment. Perceiving would involve looking at the problem, researching and talking to others. Perceiving problem solving means sitting with the assignment and walking away, shifting the process to ‘down below’ into the unconscious layers of brain activity, anfr letting the mind work through the assignment for some time without using the conscious mind.

- Integrates past ideas. Perceiving blends the past with the new assignment. Let’s say your assignment involves coming up with new ways to drive interest in a company’s new product, say men’s socks. Because you’ve worked on many, many projects with the assignment of driving awareness, you know the tried-and-true steps. But wait, you’ve also seen stellar and creative work done in financial services lately that raised awareness about products, too. While not the same product, they had similar market problems and they tried x, y or z. Integrative thinking brings in other experiments to your problem and sees what works.

- Connects dissimilar topics. Perceiving is making mental leaps and combining with other areas. Let’s say you have a passion for travel and you read lots about the best surfing in world, which you know is in far-flung places like Taghazout, Morocco, Bundaran, Ireland or Tofino, British Columbia. You know this topic, and you’ve stuffed lots of details in your brain over the years.This “stuff” comes in handy when you are thinking about travel and surf and your sock assignment. You’ve looked at the sales figures, the average consumer and you’ve got a stack in your drawer at home and the office. You realize that connecting the socks that fold easily can be found in the dark easily and are made of breathing micro-fibers with travel and these often unheard-of places could breathe new market life for the socks, and make the client very happy.

That’s perceiving — seeing the world in a new way. Utilizing your brain’s functions and harnessing your creative powers.

So what’s your take on the world around you? Do you see or perceive?

— Kate Canada Obregon